Alcohol consumption can have profound and lasting effects on the liver, the body’s primary organ for detoxification and metabolism. When alcohol is metabolized, it generates toxic by products that trigger fat accumulation, inflammation, and scarring changes that can progress over time to cirrhosis or even liver cancer. Research consistently shows that no amount of alcohol is completely safe, as risk begins to rise even at low levels of intake. Individual vulnerability varies depending on genetic makeup, dietary habits, underlying metabolic health, and drinking patterns, making some people far more susceptible to liver damage than others.

Key Takeaways

- Liver damage risk rises with both quantity and binge drinking.

- No type of alcohol (beer, wine, or spirits) is safer than another.

- Metabolic factors like obesity and diabetes amplify alcohol’s liver harm.

- Genetics such as PNPLA3 and ALDH2 variants increase susceptibility.

- Complete abstinence is the most effective treatment and prevention step.

- Coffee and good nutrition support liver recovery but cannot replace abstinence.

What Is Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease (ALD)?

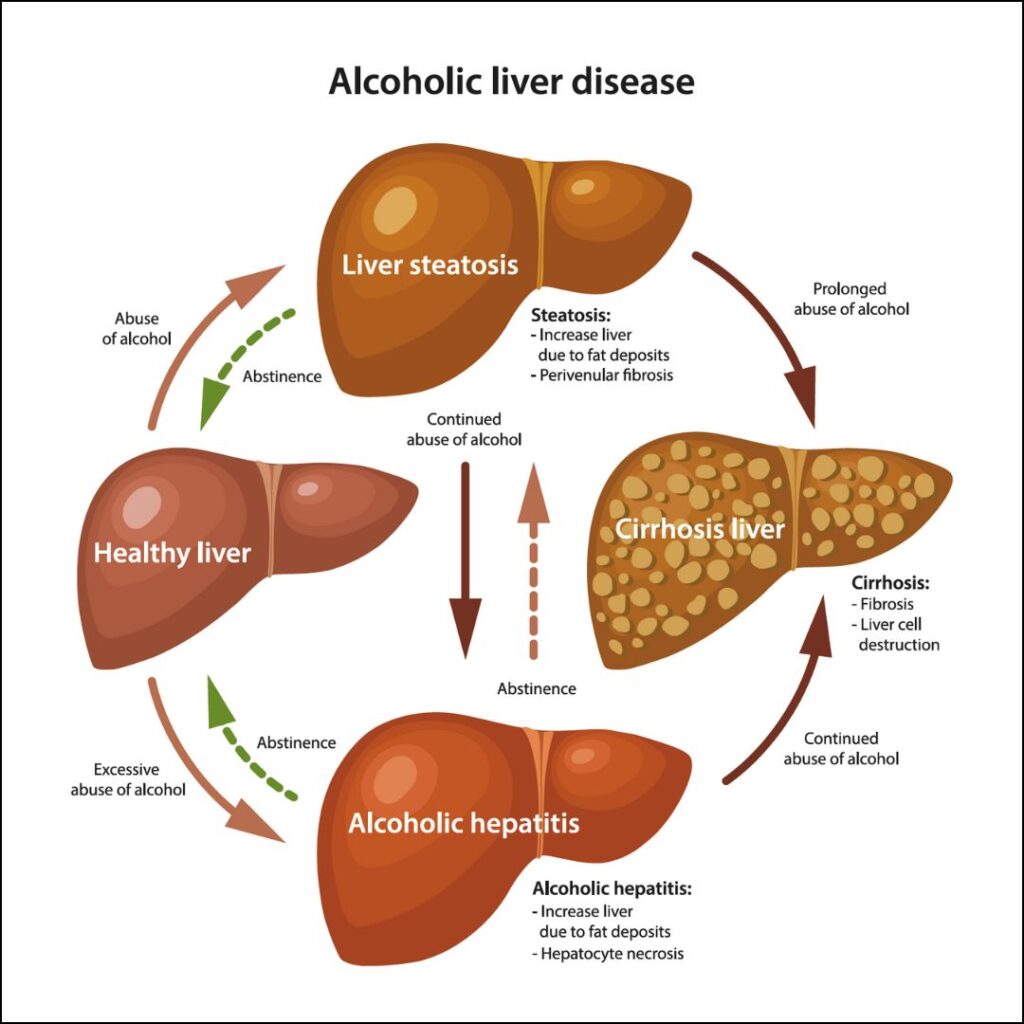

Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease is a spectrum of conditions caused by chronic alcohol intake.

It begins with fat accumulation in liver cells (steatosis), can progress to inflammation (steatohepatitis), fibrosis, cirrhosis, and in some cases liver cancer.

Key things to note:

- ALD overlaps with metabolic liver disease (in people with obesity, diabetes).

- The term “MetALD” is emerging to describe coexistence of metabolic dysfunction plus alcohol damage.

- ALD must be distinguished from viral, autoimmune, or cholestatic liver diseases.

How Alcohol Damages the Liver

The liver is the primary organ responsible for metabolizing alcohol. Chronic or excessive alcohol consumption overwhelms its capacity, leading to structural and functional damage through several mechanisms.

1. Fat Accumulation (Steatosis)

When alcohol is metabolized, it produces acetaldehyde and increases the NADH/NAD⁺ ratio, which disrupts normal fat metabolism. This causes fat to accumulate in liver cells, a condition known as alcoholic fatty liver. Fat accumulation makes liver cells vulnerable to inflammation and injury.

2. Oxidative Stress

Alcohol metabolism generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), highly reactive molecules that damage cell membranes, proteins, and DNA. Over time, oxidative stress leads to liver inflammation, cell death, and fibrosis.

3. Acetaldehyde Toxicity

Acetaldehyde, a byproduct of alcohol breakdown, is highly toxic. It binds to proteins and DNA, forming adducts that impair liver function, trigger immune responses, and promote inflammation.

4. Inflammation (Alcoholic Hepatitis)

Alcohol stimulates the immune system and gut-derived endotoxins reach the liver, activating Kupffer cells (liver macrophages). These cells release inflammatory cytokines, leading to alcoholic hepatitis, which can cause liver pain, swelling, and dysfunction.

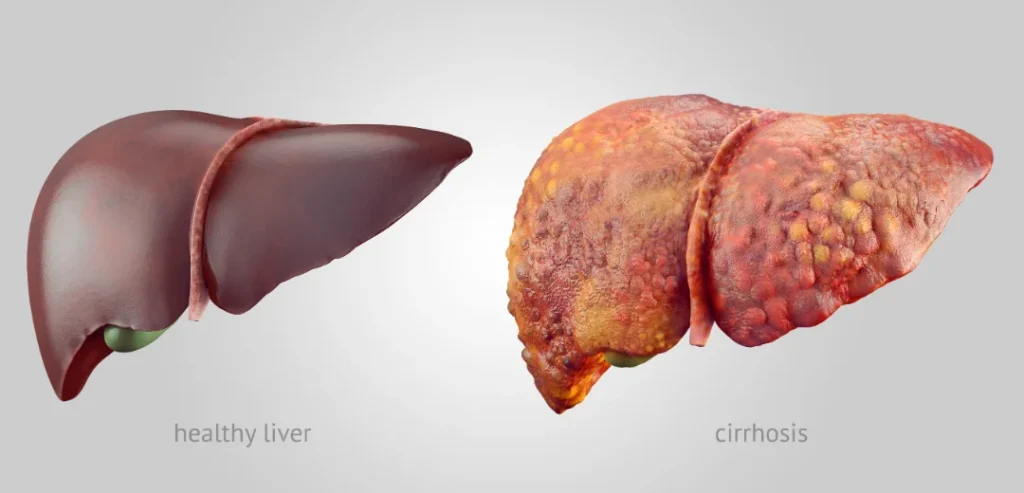

5. Fibrosis and Cirrhosis

Chronic inflammation activates stellate cells in the liver, which produce collagen. Over time, this leads to fibrosis (scarring). Advanced fibrosis can progress to cirrhosis, a condition in which normal liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue, severely impairing liver function and potentially causing liver failure.

6. Impaired Regeneration

Alcohol interferes with the liver’s ability to regenerate by affecting cell signaling and growth factors, reducing the organ’s capacity to repair itself after injury.

Global Burden and Patterns

The number of people suffering from ALD and its complications is rising. In many countries, liver transplantation is now heavily driven by alcohol‐related disease.

Age, sex, drinking norms, and cultural differences shape risk globally.

Key observations:

- Men generally have higher incidence, but women are more vulnerable per unit of alcohol.

- In parts of Europe, Latin America, and Asia, ALD accounts for a large proportion of liver cirrhosis cases.

Dose, Thresholds, and Risk Curves

Understanding how alcohol dose relates to liver risk is essential, as harm does not occur suddenly but accumulates over time. Even moderate or occasional drinking can contribute to liver stress, especially when combined with other risk factors such as obesity or poor diet. No magic “safe level” exists beyond doubt. Alcohol’s risk is dose-dependent but continuous.

- Many studies show that risk for cirrhosis rises significantly at consumption of 20–30 grams/day in women and 30 to 40 grams/day in men.

- Even low levels are associated with increased risk of certain cancers and liver injury.

- Drinking with meals or spreading consumption does not fully eliminate risk; the total volume matters more.

- Frequency and binge episodes (large amounts occasionally) add extra risk beyond average volume.

Why Pattern Matters: Binge vs Regular Drinking

The pattern of alcohol consumption has a major impact on liver health, beyond just the total quantity consumed. Irregular heavy sessions place sudden metabolic stress on the liver, disrupting its ability to repair and detoxify efficiently over time. How you drink is as important as how much you drink.

- Binge drinking (e.g. 4–5+ drinks in a single session) causes spikes in liver stress, oxidative injury, and endotoxemia.

- Cohort data show that binge patterns raise the risk of progression faster than steady moderate intake.

- Genetic susceptibility plays a role: people with risk alleles plus binge behavior can have multiplicative risk.

Metabolic Add-on: When Alcohol and Fat Meet (“MetALD”)

Many people who drink also have obesity or metabolic syndrome features. This overlap modifies the risk.

- Underlying insulin resistance, fatty liver, or obesity increases susceptibility to alcohol injury.

In some people, mild drinking that might be tolerated in lean, healthy individuals becomes harmful in the metabolic context. - Clinicians increasingly recognize the MetALD phenotype: both metabolic and alcohol insults drive damage.

Genetic Susceptibility: Why Some Are More Vulnerable

Not everyone who drinks heavily gets liver disease. Genetics helps explain variation.

- PNPLA3 (I148M variant) is the strongest known risk allele: carriers are more likely to develop steatohepatitis and fibrosis.

- Other genes: TM6SF2, HSD17B13, and alleles affecting alcohol metabolism (ADH/ALDH) modify risk.

- For example, ALDH2 deficiency (common in East Asians) leads to buildup of acetaldehyde, amplifying damage.

- In the future, risk models combining genetics + biomarkers may help tailor advice.

Diagnosis and Staging in Practice

Practical tools help in clinics and hospitals to assess severity and make decisions.

- History & Drinking Pattern: Clinicians quantify units, duration, binge episodes, and corroborate with family or biomarkers.

- Laboratory Tests: AST/ALT ratio (often AST > ALT in alcohol injury), GGT, bilirubin, INR, platelet count, albumin.

Fibrosis scores: FIB-4, APRI. - Imaging & Elastography: Ultrasound, transient elastography (FibroScan) measure stiffness (fibrosis) and controlled attenuation (steatosis).

These help stage disease noninvasively. - Severity Scores for Acute Injury: In alcoholic hepatitis, scores like Maddrey’s Discriminant Function or MELD guide treatment and prognosis.

The Power of Abstinence

Among all available interventions for alcohol-related liver disease, complete abstinence remains the single most powerful step toward recovery. It allows the liver to rest, regenerate, and gradually reverse many of the biochemical and structural changes caused by alcohol exposure.

- Even in advanced disease, abstinence improves survival, reduces decompensation risk, and may allow partial regression of fibrosis.

- Enzyme normalization often occurs in weeks to months.

- The magnitude of benefit depends on disease stage at abstinence start.

Treating AUD in Patients with Liver Injury

Managing AUD in patients with liver disease requires a multidisciplinary and individualized approach, balancing alcohol cessation with liver safety.

1. Medications

- Naltrexone: Effective for reducing cravings but can be risky in moderate-to-severe liver disease.

- Acamprosate: Safer for the liver, though caution is needed in patients with kidney problems.

- Gabapentin: Not metabolized by the liver, making it safer in liver impairment.

- Baclofen: Emerging evidence supports its use in cirrhotic patients.

2. Behavioral & Psychosocial Support

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), motivational interviewing, and mutual aid groups are essential to support abstinence and prevent relapse.

3. Withdrawal Management & Monitoring

- In hospitalized patients or those with decompensated liver disease, careful monitoring is critical during alcohol withdrawal.

- Biomarkers such as PEth, EtG/EtS, and CDT help confirm abstinence or detect relapse.

Nutrition, Coffee, and Supportive Measures

Optimal liver recovery requires a comprehensive approach that goes beyond simply avoiding alcohol. Proper nutrition, lifestyle adjustments, and supportive habits play a crucial role in restoring liver function, maintaining muscle mass, and reducing the risk of further damage or complications.

- Nutrition & Muscle Preservation

Many patients are malnourished; protein intake must be sufficient to prevent muscle wasting (sarcopenia).

Micronutrients, especially B vitamins and thiamine, must be addressed. - Coffee

Multiple observational studies show coffee consumption is associated with lower risk of fibrosis progression and HCC.

Two to four cups a day often cited; mechanism likely antioxidant and anti-inflammatory. - Avoiding Other Liver Stressors

Control of hepatitis viruses, use of hepatotoxic drugs, weight control, controlling metabolic risk factors.

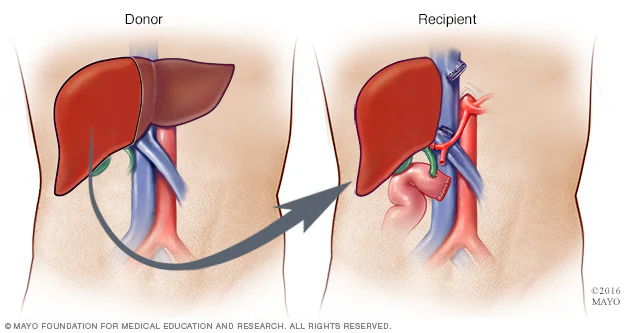

Liver Transplantation: Rethinking the “6-Month Rule”

In the past, transplant centers required six months of abstinence. This is evolving.

- Many centers now use individualized evaluation rather than a rigid cutoff.

- In severe alcoholic hepatitis unresponsive to treatment, early transplantation in carefully selected patients has shown promising outcomes.

- Psychosocial assessment, continuous follow-up, and relapse prevention are critical.

Prevention and Public Health Interventions

Reducing alcohol’s harm is not just medical it’s social and policy-driven.

- Policies like minimum pricing, restricted availability, labeling, and taxation help reduce consumption at population level.

- Brief interventions in primary care (screening, counseling) significantly reduce heavy drinking.

- Public awareness of “no safe level” for alcohol in some guidelines is rising.

Support and Resources

Recovering from alcohol-related liver disease is challenging, but reliable help and guidance make a major difference. Medical supervision is the safest way to reduce or stop drinking, especially for heavy users. Detoxing alone can be dangerous, so involving a doctor early is essential.

Structured counseling, therapy, and community programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and SMART Recovery provide long-term support. Many hospitals have liver or addiction clinics that treat both liver disease and alcohol dependence together.

For credible information and assistance, visit the World Health Organization (WHO), American Liver Foundation, or National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). Family encouragement and community support play a vital role in lasting recovery. Seeking help early is the first step toward better liver health.

Myths vs Facts

Below are common beliefs and what the evidence truly shows.

| Myth | Reality / Fact |

| Wine or beer is safer than spirits | Risk depends on ethanol dose not drink type |

| Moderate drinking is safe for the liver | No conclusive “safe level”; risks begin even at low intake |

| Only heavy daily drinkers get cirrhosis | Binge patterns and metabolic risk enhance harm |

| A good diet or exercise protects my liver against alcohol | Metabolic risk factors worsen alcohol toxicity |

| Liver always fully regenerates after stopping alcohol | Early disease may reverse, but advanced cirrhosis rarely fully recovers |

| Detoxes or herbal supplements can “cleanse” the liver | No scientific support only abstinence matters |

| You must be abstinent 6 months to qualify for transplant | Many centers now use individualized criteria |

| Coffee is harmful in liver disease | Studies suggest coffee is protective against fibrosis and HCC |

| Genetics don’t matter | Variant alleles like PNPLA3, ALDH2 meaningfully change risk |

| Drinking with meals nullifies harm | Meal timing does not eliminate dose‐dependent damage |

Practical Checklist: Assessing Your Liver Risk

Use this self-check list to consider your risk and next steps:

- Weekly alcohol units + frequency + binge episodes

- Metabolic factors: obesity, diabetes, high lipids

- Family history or known liver disease

- Symptoms: fatigue, abdominal discomfort, yellowing

- Routine labs if available: AST, ALT, GGT, platelet count

- Imaging: ultrasound or elastography if accessible

- Plan: discuss abstinence, follow up with clinician, monitor biomarkers

Conclusion

Alcohol’s role in liver disease is clear: it is a major cause of preventable liver damage worldwide. The idea of “safe drinking” is misleading, as even moderate intake can harm the liver, especially when combined with poor diet, obesity, or genetic vulnerability. While early liver injury can sometimes reverse with complete abstinence, advanced scarring or cirrhosis requires long-term management and, in some cases, liver transplantation. Awareness, early testing, and honest discussions about alcohol habits are crucial. Real protection comes not from detoxes or supplements, but from sustained abstinence, balanced nutrition, and lifestyle changes that give the liver a chance to heal.

FAQs

How many grams of alcohol per day significantly raise cirrhosis risk for men and women?

Many studies show risk increases at 20–30 grams/day in women, 30–40 grams/day in men. Risk rises steadily beyond that.

Is any alcohol intake considered safe for the liver in 2025 guidelines?

No guideline can claim a truly safe level. Recent WHO statements emphasize that no amount is completely without harm to health.

Which drinking pattern (daily vs binge) more strongly predicts liver damage?

Binge drinking (large amount in short time) tends to provoke spikes of injury and inflammation, accelerating progression more than low steady intake.

How does metabolic dysfunction change alcohol risk, and what is MetALD?

Metabolic dysfunction (insulin resistance, obesity, fatty liver) amplifies alcohol damage. MetALD describes the overlap of alcohol-related injury and metabolic disease.

Which genetic variants matter most for liver risk?

PNPLA3 (I148M) is the main known risk gene. Others include TM6SF2, HSD17B13, and variants in ADH/ALDH that affect ethanol metabolism.

What objective tests verify abstinence or relapse?

Common biomarkers include PEth (phosphatidylethanol), EtG/EtS (ethyl glucuronide / sulfate), CDT (carbohydrate deficient transferrin), GGT, and indirect lab patterns.

Which alcohol treatment medications are safer when the liver is damaged?

Safe options include acamprosate (less hepatic metabolism), gabapentin (no direct liver metabolism), and cautious use of baclofen. Naltrexone must be used carefully in liver patients.

How quickly do liver enzymes and fibrosis improve after abstinence?

Enzyme levels often normalize within weeks-months. Fibrosis regression depends on baseline damage; early stages may partially reverse over years.

Do coffee or diet changes reduce fibrosis or cancer risk in drinkers?

Yes observational data supports coffee’s protective association. Healthy diet, control of metabolic disease, and weight loss also help.

What is the status of the “6-month rule” for transplant listing?

Many transplant centers now favor individualized evaluation rather than rigid 6-month abstinence. Selected patients with severe disease may be listed earlier.

Aubrey Carson is an RDN with 9 years across hospital, outpatient, and private practice settings. They earned an MS in Clinical Nutrition from Tufts University – Friedman School (2016) and completed a Dietetic Internship at Mayo Clinic. Aubrey specializes in micronutrient assessment, evidence-based supplementation, and patient education. Their work includes CE presentations for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and collaborations with Mass General Brigham on nutrition education resources.